Protecting the Perfusion Field: How to Navigate the ECMO Staffing and Funding Crisis

Introduction to ECMO

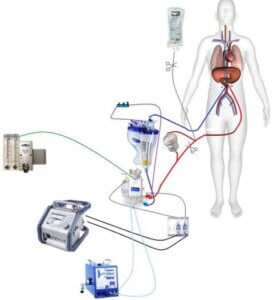

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, is a life support technique used to deliver extracorporeal cardiovascular and pulmonary support using hemodynamic care and gas exchanges. Traditionally, perfusionists—highly specialized medical professionals who undergo approximately six years of training to earn their title—have been responsible for ECMO staffing which entails the initiation, monitoring, and troubleshooting of the heart-lung machines necessary to stabilize cardiac and respiratory patients in and out of the operating room.

However, perfusionists also perform duties outside of ECMO monitoring ranging from the operation of cell savers to administration of chemotherapy drugs and support of liver transplant patients.

An Evolving Medical Landscape

In recent years, the demand for ECMO has grown tremendously, particularly in cardiac treatment facilities and especially in the United States, where heart disease is the leading cause of death. In fact, the use of ECMO therapies increased by 433 percent from 2006 to 2011. Unfortunately, the availability of certified perfusionists has not grown to match that demand. As of April 2016, only 4,096 certified perfusionists were currently practicing in the US.

Due to the discrepancy between demand and availability, simplification of ECMO technology, increased use of ECMO outside of the operating room, concerns about the cost of perfusionist-only ECMO care models, and the availability of standardized ECMO guidelines that improve patient outcomes, the perfusion field is experiencing rapidly shifting trends in care standards.

In reaction to these changing trends in technology, availability, and demand, many hospitals and medical institutions are considering a responsibility-sharing model between nurses and perfusionists to more evenly distribute maintenance care of ECMO patients and reduce the costs associated with perfusionist-only care. Further, some institutions are leaning toward a nurse-managed (as opposed to nurse-assisted) model where perfusionists are available only as off-site, as-needed contractors.

Due to this rapidly changing landscape, the perfusion field as we know it has a relatively uncertain future. We’ve compiled a comprehensive analysis of the risks and benefits of the new responsibility-sharing models that highlight the importance of protecting perfusionists’ involvement in ECMO staffing while identifying cost-saving measures that increase ECMO affordability without decreasing patient outcomes.

The Draw of Responsibility-Sharing Models

Cost-Savings as a Catalyst for Responsibility-Sharing ECMO Care Models

Medical professionals are under continuous pressure to decrease costs without endangering positive patient outcomes. We see it in the push to keep patient appointments in doctors’ offices under fifteen minutes. We also see it in hospitals’ hesitancy to perform non-urgent testing on ER visitors and in the increasing popularity of replacing intravenous (IV) specialists with across-the-board IV training for nurses.

And, now, we see it in the experimental utilization of registered nurses as the primary bedside monitors of cardiovascular ECMO patients. Research performed by Thomas Jefferson University’s Department of Surgery proves the undeniable cost-saving potential of this model; in 2010, they implemented educational programs and dedicated spaces to transition from perfusionist-managed bedside monitoring of ECMO patients to nurse oversight of patients at the bedside. Jefferson’s study produced a cost savings of $366,264 (61 percent).

That’s an impressive number. However, surface-level cost savings don’t necessarily equate to long-term profitability. Michael Hancock, Operations Manager at Keystone Perfusion Services, says the crux of the cost-saving issue is that “there are three main components at play here: safety, quality of patient care, and cost. Unfortunately, one or more of these factors is sacrificed with each [ECMO care] option…ECMO programs, if set up correctly, can be very profitable. And the concept that must be understood is that perfusionists improve the quality of care given to the patient, which leads to better outcomes, which can mean more profits to hospitals.”

There is simply no way to replicate the initial cost-savings associated with migrating minute-to-minute ECMO care from perfusionists to RNs. Evan Gajkowski, ECMO Coordinator for Geisinger Health System, reminds us that the cost of retaining on-site perfusionists is due to their unique ability to manage and troubleshoot heart-lung machines in a way that nurses and doctors simply can’t. He says, “the last thing we should even be mentioning is cutting out perfusionists from our programs. Although it costs more to have perfusionists run ECMO full-time in crisis situations and times when minutes count for everything, you want perfusion readily available for assistance.”

In other words, while utilizing nurses for routine monitoring in non-emergency situations has obvious economic merits, emergency situations can arise unexpectedly and in an instant. Thus, it’s crucial to consider the extra cost of on-site perfusionist availability a safeguard against emergencies that nurses simply cannot remedy effectively.

Reduced Stress on Perfusionists’ Schedules is Another Compelling Argument for Nurse Oversight

However, money isn’t the only consideration swaying administrators toward a responsibility-sharing model between perfusionists and nurses. Anyone in the medical field understands the tremendous stress placed on clinicians’ personal lives, schedules, and physical health. The lives of perfusionists are no exception.

Craig Matthews*, chief of a US-based perfusion program, notes that perfusionists with the added responsibility of constant monitoring of ECMO patients commonly perform 12-hour shifts. In cases where perfusionists are responsible for OR and general ECMO monitoring from insertion to removal, “perfusionist[s are] left to sleep off and on to keep ‘rested enough’ to be of some service the next day. Nursing calls the sleeping perfusionist for every beep.”

Clearly, this kind of “always-on” schedule isn’t sustainable for personal lives, personal health, or the safety of perfusionists’ patients. By effectively training and mindfully utilizing nurses for ECMO staffing, Matthews says, a perfusionist’s “handing over [of] a case allows the salaried perfusionist to maintain their life and work schedule without impacting income.”

Additionally, he says, it allows them to focus more energy on their many other duties throughout their shift that go beyond routine ECMO monitoring—namely, their responsibilities to cardiovascular and respiratory surgeries, liver transplant patients, the operation of cell savers, and the initial placement of patients onto ECMO machines

Protecting the Perfusion Field is Crucial to Maintaining Positive Patient Outcomes

However, as Keystone Perfusion’s Michael Hancock emphasized, with these potential benefits come enormous responsibility.

The Burden On (and Risk of Utilizing) Nurses for ECMO Staffing

Part of the reason why transitioning care of ECMO patients from perfusionists to nurses post-insertion has the potential to save hospitals so much money is that nurses represent a fixed, mandatory cost. Therefore, while the presence of perfusionists can be perceived as an “additional” cost, adding additional responsibilities to nurses’ rotations does not necessitate an increase in nurse salaries. Essentially, administrators then get a previously expensive “something” for closer to “nothing”—but this savings, like most cost-reductive measures, is not without its risks.

First and foremost, administrators mustn’t overlook the fact that nurses are often under as much pressure in both workload and shift length as perfusionists. Like perfusionists, their shifts are often 12-13 hours in length, and they often work several very long days in a row. Therefore, their potential to overlook warning signs in patients or make errors is at least as high as a perfusionist’s; it’s made higher than a perfusionist’s by their comparative lack of appropriate training.

Michael Hancock explains that, “the way nurse-driven ECMO works is that the normal nurse that takes care of the patient is also responsible for monitoring the ECMO machine, so there is no increase in cost to the hospital. The problem is that ECMO patients are incredibly labor-intensive to care for, especially from a documentation standpoint. Nurses have far too much responsibility for taking care of these patients just doing their normal duties. Adding a complex machine such as dialysis and the ECMO machine is simply too much.”

His mention of the labor required to properly care for an ECMO patient brings us to the next problem with nurse-driven ECMO: there is, quite simply, a higher potential for error when hospitals train nurses and ICU staff in a field outside of their range of expertise. Added stress alone creates this danger, but perfusionists are the only medical staff in a hospital equipped with the technical, medical, and problem-solving training necessary to ensure that nothing goes wrong during the sometimes precarious recovery of ECMO patients.

So, while nurses can be safely trained to monitor ECMO patients for basic equipment anomalies (and to activate a call tree to employ the appropriate clinician when something goes wrong) after the crucial first eight hours on a machine, a hospital should never be without a perfusionist on-site to make routine rounds of checks on these patients and to respond immediately for troubleshooting.

If a patient is on ECMO, says Hancock, “there must be a perfusionist in the hospital…no matter how stable the patient may be, there is always the risk of equipment malfunction, inadvertent circuit fracture, and other troubleshooting needs…a perfusionist is the only qualified clinician to rectify these issues in enough time to save a patient’s life.”

Updated Technology Is Key to the Utilization of Nurses for ECMO Staffing

As more and more hospitals answer the calling for a partnership in patient monitoring between perfusionists and nurses, it’s important to note that a nurse oversight model can only be successful if the newest ECMO equipment is employed. Older technology, while safe in the hands of a certified perfusionist, leaves too much potential for equipment failure or errors that a nurse isn’t trained to remedy.

Realistic Ways to Solve the ECMO Staffing Crisis and Relieve Hospitals’ Financial Burden Without Sacrificing Quality of Care

Previously, survival rates for ECMO patients varied widely. This is likely due in part to the lack of standardized procedures across ECMO programs and the continuous shortage of ECMO-qualified personnel. The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) took steps to remedy this issue by releasing new guidelines that allow nurses with one year or more of critical care experience to take part in ECMO training

Of course, this kind of specialized training may quickly become expensive enough to offset the cost savings of reduced perfusionist utilization.

A Partnership Between Perfusionists and Nurses is the Only Long-Term Solution for ECMO Staffing

Now that a cost-saving opportunity has been identified, it cannot be forgotten. Instead, we must strive to protect the perfusion field and the specialized knowledge it carries while reducing costs to hospitals, maximizing clinicians’ quality of life, and protecting the safety of ECMO patients above all else.

Hospital administrators generally agree that, as long as there is a patient on ECMO, there must be a perfusionist in-house to respond to emergency situations in time to save that patient’s life. As technologies continue to improve and program restructuring becomes a possibility, it may be possible to reconsider this, but there is currently no one else in a hospital setting that can reliably re-stabilize a critical ECMO patient.

Many hospitals have found a middle ground in one of several ways. Some, for example, have nurses trained to sit bedside with ECMO patients and a perfusionist in-house that makes routine checks for as many as four ECMO patients at a time. This model ensures that perfusionists are freed up to complete their many other duties without neglecting the need for constant monitoring of ECMO patients; and, should an urgent situation arise, the perfusionist can respond and remedy it immediately

Other hospitals will have the perfusionist sit bedside for the first eight hours after insertion and, once they can confirm that the patient is in stable condition, they will pass off minute-to-minute monitoring of the patient for the duration of treatment.

In both situations, the hospital only has to pay the perfusionist for the initial implementation period and, in the case of the second, for the first eight hours after insertion. This allows hospitals to achieve financial savings without sacrificing patient safety or destabilizing the viability of the perfusion field.

Some hospitals, however, are attempting to do away with perfusionists altogether for non-emergency situations, and even the thriftiest of administrators admit that this could become a slippery slope.

One interviewee states, “We must ensure that ECMO staffing and monitoring stays perfusion driven. We must be like the respiratory therapy field and own our machines and the monitoring that goes with it. Nurses are not allowed to touch the ventilator. That responsibility is solely that of the respiratory therapist. That is how it should be with ECMO. If we do not own this, where does it stop in terms of allowing other unqualified clinicians to operate extracorporeal technology? Will we eventually let nurses run the heart and lung machine during cardiac surgery?”

The answer should, without question, be a resounding “no”. While shifting priorities, updates in technology, and opportunities for cost savings necessitate that all elements of a care team remain adaptive to change to survive, it is unwise and dangerous to patient outcomes to eliminate the sole specialist in existence capable of managing specialized patient needs—of any kind.

Secondly, it’s important to remember that nurses are specialists in their own right and that it is unfair—and ill-advised—to expect them to take on an entirely different specialty in the same amount of work time without an increase in pay or comprehensive training. Adding responsibility like this means less time to do what it is that they do best—nursing—and a subpar ability to do the new task being asked of them, ECMO monitoring.

Before long, a model requiring such an increase in responsibility would lead to the same dangers as overworking perfusionists by requiring them to perform constant bedside monitoring in addition to their other duties.

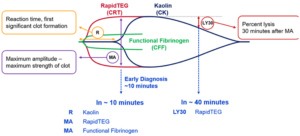

Craig Matthews, perfusion program chief, also reminds us of a fundamental and important difference between perfusionists and nurses: “Nursing loves structured process and procedure. Perfusionists, in general, trust their judgments. Both can get an hourly gas or activated clotting time, [but] a perfusionist will know what it means and make adjustments.” In Matthews’ program, nurses are trained to identify and note a red flag during their monitoring and to call an intensivist to make changes accordingly.

Because of this kind of fundamental difference in approach (and knowledge), it is important to think of nurses and perfusionists as complimentary members of a team rather than equal providers of the same service. It is impossible to solve the ECMO staffing problem by creating more perfusionists or increasing the availability of perfusionist certification schools because, as Michael Hancock puts it, “the amount of perfusion schools in the country is limited and that probably will not change due to the lack of profitability of those programs.”

Instead, we must strive to meet the field-wide calling for cost reduction in ECMO and beyond without putting the highly specialized and irreplaceable perfusion field on the chopping block or sacrificing the quality of care. The only safe way to do this is to invest in quality academic, laboratory, and field education for nurses before easing them into unsupervised monitoring of stable ECMO patients. In doing so, it’s important to remember the wide array of specialized technological and medical knowledge brought to the table by perfusionists to keep them on-site, on-staff, and available to assist patients.

Otherwise, as Matthews states, “perfusionists can push themselves out of this market over the next decade if they’re not careful.” That’s why it’s so important to refine the quality of care standards when transitioning nurses into the ECMO care team.

Because if quality of care goes down, the profitability of ECMO programs and hospitals as a whole will suffer, and the new responsibility-sharing models will have been for naught.

*Name has been changed at the interviewee’s request.

Keystone Perfusion is a full-service perfusion staffing provider. We specialize in providing perfusionists to hospitals and health systems for ECMO staffing. Contact us today to discuss staffing options.