Fifty Things a Cardiac Surgery Team Can Do for Blood Conservation

blood conservation

|

By: Russell F. Stahl, MD, Director Cardiac Surgery Grand Strand Medical Center |

Overall

The transfusion of autologous blood remains a potentially controllable complication of open-heart surgery. The most important element in a blood conservation program is an attitude on the part of the Cardiac team to simply avoid unnecessary transfusions. If the entire team is devoted to blood conservation, the greatest reduction in transfusion and largest benefit to the patient can be achieved. Here, our team sets forth 50 techniques that can contribute to blood conservation during open heart surgery. While some of these techniques may seem obvious, trivial or mundane, it is our opinion that blood conservation stems from not one big thing, but multiple smaller endeavors.

Preoperative Techniques

- Ensure the highest hematocrit possible entering the operating room

This is easier to do on elective operations which allow more time for investigation and treatment of anemia, but many of the measures listed below can be applied to either outpatients or inpatients prior to surgery. Especially, attention to iron stores and anemia of inflammation guides preoperative treatment. All anemic patients should receive consideration of the morphologic type and potential cause of anemia. Consultation with a hematologist or nephrologist (for patients with kidney disease) may be helpful.

- Minimize blood draws during the preoperative workup

Those issuing preoperative orders should be thoughtful about which blood tests are necessary and which have already been done, or are not truly needed. Coordination with other clinicians is important.

- Use pediatric tubes for blood draws

Requires an institutional laboratory commitment.

- Use oral iron, folic acid and vitamin C supplements liberally

While more time between initiation of treatment and surgery is helpful, these benign and inexpensive oral medications can be started on most patients at any time. Anticipating that all patients will experience some anemia after surgery, pre-operative and post-operative treatment may help mitigate that anemia.

- Use intravenous iron supplements

Absorption of oral iron may be impaired, particularly in patients with chronic illness. We prefer a parental iron supplement that causes few side effects and does not require pre-treatment to prevent reactions. Intravenous iron is especially helpful in the hospitalized anemic patient, perhaps with underlying renal disease or low iron stores. Intravenous iron can also be used post-operatively to replete iron stores and accelerate red cell production.

- Use erythropoiesis-stimulating agents as indicated

Although controversial for ICU patients, there are some patients who can benefit from erythropoietin analogs to build red blood cell mass before surgery. Recent trials have suggested a preoperative strategy of treating anemia (hemoglobin <12 g/dl) or isolated iron deficiency with a cocktail of therapies that included subcutaneous EPO, vitamin B12, intravenous iron, and oral folic acid given the day before surgery. Compared with the placebo control group, the intervention group had fewer red blood cell transfusions in the first 7 days and adverse events were comparable.

- Optimize the patient’s hemostatic system before surgery

The following measures are designed to reduce intra-operative and post-operative bleeding by minimizing avoidable hemostatic deficiencies.

- Stop all anticoagulants at the appropriate time (see chart)

For vitamin K antagonists, the larger the dose of warfarin, the less time that is required for the INR to return to baseline. Although different surgeons have different thresholds for proceeding with surgery, we generally look for an INR less than 1.3. Oral or parenteral supplements of vitamin K may hasten the normalization of INR, but can delay re-anticoagulation postoperatively.

| Clopidogrel (Plavix) | Inhibits ADP receptor on platelets

Stop 5 days prior to surgery in elective patients Stop 24 hours prior to surgery in urgent CABG |

| Prasugrel (Effient) | Inhibits ADP receptor on platelets

Stop at least 7 days prior to surgery |

| Ticagrelor (Brilinta) | Inhibits ADP receptor on platelets

Stop 5 days prior to surgery in elective patients Stop 24 hours prior to surgery in urgent CABG Do not take more than 100mg Aspirin per day with Brilinta |

| Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) | Factor Xa inhibitor

Stop 24 hours prior to surgery |

| Dabigatran (Pradaxa) | Directly, reversibly inhibits thrombin

Stop 1-2 days prior to surgery if GFR>50 Stop 3-5 days prior to surgery if GFR<50 |

| Apixaban (Eliquis) | Factor Xa inhibitor

Stop 48 hours prior to surgery |

| Cilostazol (Pletal) | Inhibits phosphodiesterase type 3

Stop 2-3 days prior to surgery |

| Abcximab (Reopro) | Reversible binds platelet glycoprotein IIb / IIIa

Stop 12 hours prior to surgery |

| Eptifibatide (Integrilin) | Reversible binds platelet glycoprotein IIb / IIIa

Stop 2-4 hours prior to surgery |

| Ticlodipine | Inhibits ADP receptor on platelets

Stop 10-14 days prior to surgery |

- Treat with vitamin K if nutritional deficiencies are suspected in patients not taking a Vitamin K antagonist.

Vitamin K dependent coagulation factors may be depleted in malnourished patients, including those with normal INR’s. In some instances, levels of Factors II, VII, IX and XI have to fall below 30% of normal to have a detectable effect on INR. Thus, treatment with Vitamin K can be helpful in patients not on warfarin who are malnourished or have modest hepatic dysfunction. Those with more severe liver disease (MELD score greater than 14) should have careful consideration regarding the overall risks and benefits of cardiac surgery.

- Check the P2Y12 (Verify now) PRU when stopping antiplatelet medication before surgery

We use a checklist to ensure that anti-platelet medications are stopped at the appropriate time before surgery (see chart). Laboratory testing can be used to confirm that the risk of bleeding has been minimized. In our institution, a PRU greater than 200 indicates that the anti-platelet effect of clopidogrel has worn off, and bleeding as a result of that drug should be acceptable.

- Hold aspirin if necessary; often aspirin is more effective as an anti-platelet medication than clopidogrel

Studies on peri-operative aspirin use for heart surgery have indicated that the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke are lowered with aspirin usage, with bleeding being slightly increased. We generally continue aspirin through surgery in patients at low risk for bleeding, but may stop it if the patient’s risk profile (bleeding versus stroke) suggests otherwise.

- Stop non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and COX-2 inhibitors at least 48 hours prior to surgery

Nearly all patients can live without these ant-inflammatory medications which inhibit platelet function for a short time.

- Minimize or stop steroids prior to surgery as much as possible

These medications impact hemostasis, as well as wound healing.

Techniques Related to Cardiopulmonary Bypass

- Develop a heparin protocol that is simple, safe and minimizes under or over anticoagulation and intra-operative testing

We prefer to avoid heparin before conduit harvest. Our routine is 400 units/kg of unfractionated heparin as the initial bolus just prior to cannulation. We maintain an ACT by point of care testing (I-stat, pre-warmed, kaolin) above 400 sec. If 400 sec is not achieved, or if the ACT goes below 400 sec during cardiopulmonary bypass, an additional 200 units/kg of heparin is administered. We feel that is usually the maximum amount of heparin to be given during a heart operation. More heparin may contribute to more bleeding, more heparin-protamine effects, and possible heparin rebound early post-operatively. If the ACT becomes sub-therapeutic again, 2 bottles (about 1000 units) of anti-thrombin III are immediately administered to the patient (we keep this nearby in the O.R.). Heparin resistance should be anticipated in patients with chronic illness, malnutrition, low serum proteins, endocarditis and those exposed to intravenous heparin infusions for days prior to surgery. Heparin resistance not responsive to our protocol has been extremely rare in our experience, and is treated with additional ATIII, additional heparin, and rarely FFP during CPB.

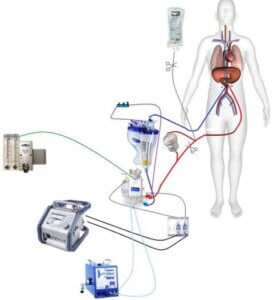

- Minimize the cardiopulmonary bypass circuit

Like most heart surgery teams, we have strived to reduce hemodilution by making the cardiopulmonary bypass circuit as small as possible. We have not gone as far as eliminating the reservoir altogether or using pediatric circuits, but we do use an integrated oxygenator with the shortest possible tubing. By using retrograde autologous priming, we can reduce the amount of crystalloid mixed with the patient’s blood upon institution of cardiopulmonary bypass to less than 1 liter.

- Discuss with the perfusion team methods to limit hemodilution

Techniques such as retrograde and antegrade autologous priming, minimizing the bypass circuit, use of biocompatible surfaces, and appropriate use of vasopressors can reduce the amount of crystalloid administration and hemodilution during cardiopulmonary bypass. Maintaining the hematocrit between 20 and 30% during CPB leads to a smoother post-operative course. Very thin blood contributes to bleeding, and bleeding begets bleeding via consumption of coagulation factors.

- Perform retrograde autologous priming of arterial and venous lines

This may require “help” from the anesthesiologist in the form of phenylephrine just before the institution of cardiopulmonary bypass

- Keep cardiopulmonary bypass times as short as possible

An obvious recommendation. However, steps such as checking and preparing the conduit (both arteries and veins), having the right personnel in the room and scrubbed, and completing any dissection required to place the aortic cross-clamp, venting cannula or other instruments and begin the actual operation, can be helpful in minimizing pump time.

- Keep hematocrit above 20% during cardiopulmonary bypass

Although the primary focus of this paper is ways to minimize blood transfusion, sometimes a well-timed transfusion can improve the overall outcome. Our team tries to keep the hematocrit above 20% during cardiopulmonary bypass. Research has shown that lower hematocrit during cardiopulmonary bypass may be associated with more bleeding, and organ dysfunction such as acute kidney injury. We will transfuse packed red blood cells before going on bypass, or add them to the heart-lung machine as we initiate cardiopulmonary bypass, to avoid severe anemia during the pump run.

- Flush the crystalloid cardioplegia to the Cell Saver to avoid wasting any blood; use blood based cardioplegia to minimize hemodilution. Longer acting cardioplegia helps minimize hemodilution and provides excellent myocardial protection.

- After infusing the blood from the heart-lung machine back into the patient post-bypass, drain the remaining fluid in the pump to the Cell Saver for processing

Intra-operative Surgical Techniques

- Stop bleeding immediately upon initiation of surgery: “Dry on the way in equals dry on the way out”

While it may seem obvious to state, careful surgery that stops bleeding immediately, can reduce cell-saver usage and loss of coagulation factors during an open heart operation. This can be done without sacrificing too much in the way of time, resulting in an overall more efficient operation. Some examples follow.

- When making the skin incision, cut through only the dermis and use the cautery (with gentle spreading of the tissues) thereafter.

The pre-sternal fat will generally fall away with minimal cauterization. Individual vessels can be cauterized or clipped in the case of large veins, common in obese patients or those with elevated central venous pressure.

- Limit the use of sponges, use the Cell Saver to scavenge every drop of blood

Perhaps surprisingly, an open heart operation can be done using only 1 laparotomy pad. By not soaking blood up into sponges and tossing them aside, more autologous blood can be returned to the Cell Saver, processed and red blood cells reinfused to the patient. Even if the lap sponge becomes saturated, it can be wrung out and reused, limiting the amount of blood that is discarded.

- If additional sponges are used, rinse them out and send the solution to the Cell Saver at the completion of the case

- Pay attention to the small crossing veins just above the manubrium and at the sternal- xiphoid junction

These veins can be anticipated and controlled during sternal entry.

- Apply bone wax to the sternal marrow

Although some surgeons believe that bone wax inhibits wound healing, we have found that a modest application at the beginning can reduce bleeding. Some of it gets removed during the course of surgery. Wound healing, with a properly closed sternum, has not been a problem.

- Gently cauterize the sternal edges

Just control individual bleeding points; do not strive for charcoal.

- Use the Cell Saver extensively and nearly exclusively while dissecting the mediastinal tissues. It can be used to retract the mediastinal fat while initiating mammary artery harvest

- Find the 2 lobes of the involuted thymic gland and gently separate them using the tip of the electrocautery; clip the crossing veins as the thymic lobes are divided.

Wherever possible, simply spread the fat out of the way without cutting it. Mediastinal fat can be separated from the pericardium in a hemostatic manner, dividing as few vessels as possible. By separating fatty tissues bluntly, rather than cutting through them, both blood and lymph leak can be reduced.

- Prior to cannulation, assess the aortic and atrial tissues; use pledgets and additional purse string sutures to limit bleeding around the cannulae.

Repair any significant leaks around cannulae at the outset, particularly if a longer pump run is anticipated (bleeding begets bleeding). Although blood leaking around cannulas can be suctioned with the Cell Saver, this leads to loss of clotting factors. Use of a cardiotomy sucker to scavange shed blood exposed to mediastinal tissues can stimulate thrombin formation and DIC-like consumption, as well as generation of inflammatory mediators, during cardiopulmonary bypass. Thus, ‘drop-in” cardiotomy suckers should be limited to the intra-cardiac chambers as much as possible (and avoided altogether on most CABG operations). Hemostatically secured cannulas are important, especially in the high bleeding risk patient.

- Check each distal anastomosis with blood cardioplegia through the graft. All surgical sites are inspected again prior to weaning from CPB.

The best time to repair leaks in distal anastomoses and other surgical sites is prior to weaning from CPB. This can avoid lifting of the heart once off bypass and speed the time to protamine reversal and “drying up”.

- Spend time drying up as needed

This can be challenging for busy surgeons who are eager to “get on to the next thing”. Even if closure is left in the hands of residents or physician assistants, taking extra time at the completion of the operation can pay dividends in terms of blood conservation. While waiting for the hemostatic system to improve, one can continue to use the cell saver and return as many RBC’s back to the patient as possible. We do not process the final bowl of cell saver blood until after the chest is completely closed and the drainage tubes have been thoroughly sucked-out. This requires a little more time, effort and commitment from scrub and perfusion staff.

- Place Surgicel between the sternal edges before closing.

Personal preference. Others prefer more bone wax, gelfoam with or without vancomycin powder, or other products. We no longer use platelet rich plasma, primarily due to inefficient cost-benefit analysis.

- Close the patient and stay in the operating room if concerned about bleeding; reopen the chest as needed, or based on initial chest tube drainage

We are not the first to suggest a “bleeding time-out” at the completion of surgery, but this can be extremely useful, particularly after a long, bloody operation. A tired team does not want to return to the O.R. a few hours later to re-explore for bleeding, and sometimes a second look at the initial trip will reassure the surgical team that chest tube drainage is due to coagulopathy and not surgical bleeding.

- Use the Cell Saver right up until the last moment

Even if this requires the perfusionist to take back already processed packed red blood cells to “make another bowl” in the Cell Saver. This may not be an issue for institutions that have continuous red blood cell processing available.

- Have a small suction catheter on the field to suck out the chest tubes repeatedly as the wound is being closed

Send every drop to the cell saver before leaving the O.R.

Medications and Blood Products used to Assist Hemostasis and Conserve Blood

- Administer just the right amount of protamine.

In our hands a ratio of 0.8mg protamine per mg (10,000U) heparin is the starting reversal dose. We do not use heparin titration curves or heparin concentrations to determine heparin dosing. We use ACT to determine therapeutic heparinization and protamine reversal. Additional protamine can be administered if the patient appears “wet” after the initial protamine dose, or if the ACT has not returned to baseline.

- Use anti-fibrinolytic medications according to STS practice guidelines

We use tranexamic acid (TXA; 1mg/kg bolus after heparin and drip at 450 mg/hr for remainder of case) as continuous intravenous infusion starting before the institution of CPB and continuing until the dose is complete, usually after CPB is terminated and the patient arrives in the CVICU.

- Use appropriate dose of DDAVP if the patient is bleeding

A class IIB, LOE B recommendation according to STS guidelines. The indication would be CPB induced platelet dysfunction in most patients. Drug reactions and risks are minimal.

- Use prothrombin complex concentrate as needed in appropriate cases

In general, PCC is used for rapid reversal of Warfarin, but there is increasing evidence of its utility for bleeding after heart surgery. A recent meta-analysis showed lower rates of transfused blood products in patients that are bleeding (by clinical assessment) after heart surgery. The 4 factor type of PCC is associated with fewer pro-thrombotic complications and is therefore considered safer. We use it in much smaller aliquots than the full weight-based dose recommended for warfarin reversal, thereby minimizing cost and potential thrombotic complications.

- Reserve the use of activated factor VII (Novo 7) for only the most severe bleeding

Activated Factor VII is also a Class IIB, LOE B recommendation for intractable bleeding after CPB. Again, we use it rarely and in the smallest amounts possible (usually 1 or 2 mg doses, rather than 70mcg/kg) to “titrate” its effect. The goal is to stop bleeding without inducing serious thrombotic complications such as stroke, DVT, or early bypass graft failure.

- If the patient is very likely to continue bleeding, “pull the trigger” on blood products early to reduce total transfusion requirement.

Combining aggressive early repletion of hemostatic factors with appropriate medications and surgical re-exploration is the best way to reduced postoperative bleeding

Postoperative Techniques

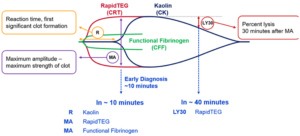

- Check the INR, platelet count and fibrinogen level upon arrival in the ICU.

These laboratory values can guide transfusion therapy. We have also used the ROTEM and TEG in the past, but still revert to multi-component therapy in most cases of serious bleeding. The use of PCC has virtually eliminated the need for cryoprecipitate.

- Have well-established transfusion protocols and practice them.

- Pay attention to the physiology of the patient as well as to the hematocrit; transfuse packed red blood cells if there are physiologic indicators or rapid continuous bleeding.

Transfusion solely for hematocrit values such as below 30% has long been abandoned. In many institutions PRBC transfusion is permissible if the hemoglobin drops below 8 in a patient with ischemic heart disease (much of our patient population), but that number may not be applicable to the post-operative patient who has been revascularized , and shows no physiologic signs of inadequate blood volume or problematic anemia.

- Scavenge the blood from the Pleur-Evacs whenever possible.

This may require keeping the Cell Saver available and determination on the part of the perfusionist to retrieve this blood; there are Pleur-Evac drainage systems that allow the blood to be retrieved more easily from the collection chamber. We do this especially when a bleeding patient is returned to the O.R. Sterility of the processed blood is maintained.

- If the patient is vasodilated, use vasopressors as opposed to excessive amounts of crystalloid fluid

- Give 1 unit of packed red blood cells at a time and recheck hematocrit and physiologic needs

- Avoid the use of “triple therapy”: Dual anti-platelet medications plus anticoagulant.

Once anticoagulation started, most patients need only low-dose aspirin. Exceptions might include patients with recently stented coronary arteries, not bypassed at the time of surgery, with indications for anticoagulation such as atrial fibrillation, high CHADS-VASC score, or mechanical heart valves.

Interactions With Others Outside of Your Team

- Convince other clinicians to minimize blood draws preoperatively

- Convince your laboratory to use pediatric tubes for blood draws

- Make sure that transfusion decisions on postoperative patients are tightly guarded

Techniques That We Have Abandoned

- Creation and instillation of platelet rich and platelet poor plasma

We used this technique for years, hoping that it would accelerate wound healing as well as minimize bleeding. However, the statistical evidence for this was quite weak and did not justify the trouble and expense.

- Aprotonin

This nonspecific serine protease inhibitor is very effective at reducing postoperative bleeding, but has been associated with other adverse outcome such as acute kidney injury. Thus, it is no longer commercially available.

- Acute normovolemic hemodilution (ANH: preoperative blood sequestration)

There are sound physiologic indications for taking some of the patient’s whole blood out prior to heparinization and cardiopulmonary bypass, and then re-infuse it at the completion of the operation. The shed blood has a lower hematocrit, and the clotting factors in the sequestered blood avoid exposure to the heart lung machine. However, the goal of maintaining hematocrit above 20% during cardiopulmonary bypass disallows this technique in many patients. Those with large blood volumes and high hematocrit entering the operating are unlikely to receive a blood transfusion regardless of utilization of ANH.

Summary and Conclusions

Most surgeons now believe in blood conservation and avoidance of unnecessary blood transfusions. Practice guidelines propagated by the Society of Thoracic Surgery are very helpful for identifying evidence-based techniques to this end. This summary describes one centers practice in utilizing those guidelines, together with other small interventions, to minimize blood transfusion. Cumulatively, these techniques have resulted in significantly lower blood utilization across the board for our open-heart surgery patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Making cardiopulmonary bypass safer, blood conservation leads to less acute kidney injury and other complications during the postoperative period. This in turn leads to shorter length of stays hand reduced cost associated with open heart surgery.

About Dr. Stahl:

Biography

Russell F. Stahl, MD, received his medical degree from New York University School of Medicine in New York, NY. He completed his internship, residency and Cardiothoracic Fellowship at Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA. Dr. Stahl is board certified in cardiothoracic surgery, and has strived throughout his career to make cardiopulmonary bypass safer by minimizing blood transfusion and acute kidney injury.

Credentials and Education

- Cornell University

Undergraduate Degree – 1979 - New York University School of Medicine

Graduate Degree – 1983 - Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Internship – 1984 - Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Residency – 1990 - Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Fellowship – 1992

The full publication is provided in Pdf format & downloadable by Clicking Here.